munmap madness

27 Jul 2016This post explores the possibilities arising from forcing free to unmap arbitrary regions of the address space and is part of the ptmalloc fanzine. While some interesting scenarios present themselves, I view this mostly as a curiosity, an educational foray into ptmalloc and the virtual memory manager subsystem of Linux. Kernel and glibc source links and statements like “the default stack size is 8MB” that are obviously platform-dependent all pertain to Ubuntu 16.04 on x86-64, unless stated otherwise. Ptmalloc and glibc malloc will be used interchangeably to refer to the malloc implementation in current glibc, while malloc in itself will refer to the malloc function.

Allocating mmapped chunks

Glibc malloc uses mmap directly in multiple cases:

- all the non-main arenas and their heaps are directly mmapped

- for chunksizes over mp_.mmap_threshold that cannot be served from the large bins or top. These chunks have the IS_MMAPPED bit set in their size field and are released to the OS upon free. This means they are never entered into any bins and the IS_MMAPED bit is ignored in every case during malloc calls. In this post we will look into ways to leverage a free call on a corrupted chunk that has the IS_MMAPPED bit set. Either originally, by the corruption, both, or by a House of Spiritesque build-a-fake-chunk-somewhere-then-pass-it-to-free situation, doesn’t matter.

It’s important to note how ptmalloc handles alignment requirements when using mmapped chunks. While mmap is guaranteed to return page-aligned regions, the user can request a greater alignment from glibc with memalign and friends. In this case an allocation with a worst case padding is obtained via _int_malloc so that a chunk of the requested size can be carved out at the required alignment boundary and returned to the user. This may mean wasted bytes at the beginning and end of the allocation, so the leading and trailing space is returned via free. However, if _int_malloc returns with an mmapped chunk, then simply the offset of the aligned chunk into the mmapped region gets stored in the prev_size field of the header. This enables free to find the beginning of the mapped region when called on the chunk (see below) while retaining support for platforms that cannot partially unmap regions (just a guess) and avoiding costly munmap calls.

Freeing mmapped chunks

__libc_free hands over chunks with the IS_MMAPPED bit set right to munmap_chunk, _int_free isn’t called in this case. munmap_chunk (abbreviated code below) only contains two integrity checks, some bookkeeping and the actual call to munmap. Note that the return value of munmap isn’t validated. The integrity checks ensure that the parameters passed into munmap are page-aligned but nothing more.

uintptr_t block = (uintptr_t) p - p->prev_size;

size_t total_size = p->prev_size + size;

if (__builtin_expect (((block | total_size) & (GLRO (dl_pagesize) - 1)) != 0, 0))

{

malloc_printerr (check_action, "munmap_chunk(): invalid pointer", chunk2mem (p), NULL);

return;

}

/* If munmap failed the process virtual memory address space is in a bad shape. Just leave the block hanging around, the process will terminate shortly anyway since not much can be done. */

__munmap ((char *) block, total_size);This means that by corrupting the prev_size and size fields of a chunk and taking advantage of the way the beginning of the mmapped region is calculated, we can unmap an arbitrary memory range from the address space, assuming we know:

- the offset of the chunk into the page containing it, to pass the alignment checks

- the distance of the target memory range and the freed chunk

These would most realistically come from two leaks, the absolute address of the chunk and the absolute address of the target. Since munmap supports partial unmappings, we can also hit a single page of a mapping if needed.

Everything below is based on this primitive, even though some examples, for brevity, use munmap directly instead of emulating the corruption and subsequent free.

Why would I want to do that?

Fair question. Well of course to map something else in place of the old data, effectively arranging for a use-after-free via the dangling references to the unmapped region.

The virtual memory manager subsystem of linux

Since I’m out of my depth here, especially on the kernel side, this will only be a short, practical overview of the virtual address space of processes and some interesting special cases. Corrections or additions are highly welcome.

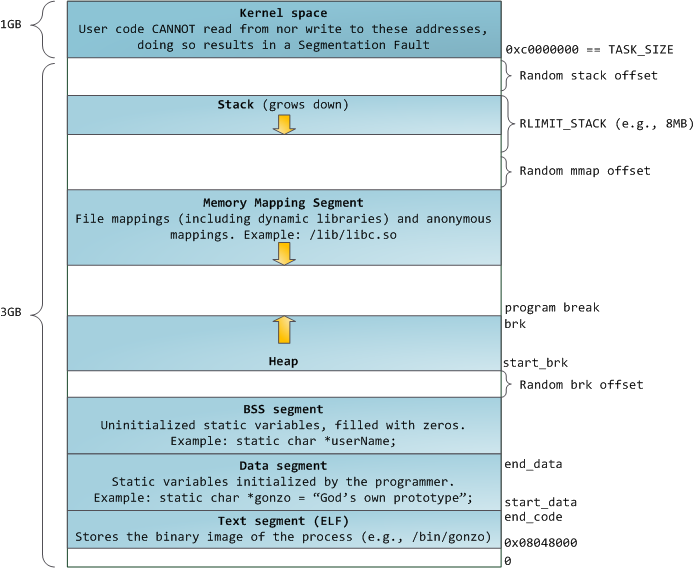

A great overview of how a program’s virtual address space looks like can be found here and additional details on the kernel side here. Let’s take a look at the following shamelessly stolen image:

The 64-bit address space layout is very similar (for our purposes) but with much more entropy. An important case not shown here is PIE binaries. If the binary image itself is position independent, two things can happen:

- it’s placed at the top of the mmap segment, with the libraries, so they share the mmap offset as their source of randomization

- it’s placed in its completely own region

See here for concrete examples. Kernels without this patch behave the first, newer kernels (e.g. the one in Ubuntu 16.04) the second way.

Some empirical observations about the mmap segment:

- it grows downwards from mmap_base, the first region that can accommodate the request is used

- consecutive mappings are placed directly below each other (keeping in mind the previous point and possible holes)

- upon reaching the lower end of the address space, bottom-up allocations take over, starting upwards from mmap_base

- the kernel is lazy: until a page is accessed, no actual physical frame is mapped to it. Because malloc will only write to the first page of a mapped chunk, if we can force large malloc calls without needing to actually touch the pages by writing data there, huge gaps can be bridged in the address space. Another thing to keep in mind is that malloc limits the number of mmapped regions to 65536.

Let’s see this in practice, by continuously mmapping 32MB regions until we run out of address space. and observing when the ordering of the returned addresses change (switching to bottom-up upon reaching the bottom of the address space) or when consecutively returned address are non-contiguous (bumping into another region, e.g. the binary or the stack):

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ ./exhaust

First mapping: 0x7fe81bbb8000

Non-contiguous mmap: 0x5578825b1000 after 0x557887bb8000

Non-contiguous mmap: 0x7fe81e1a9000 after 0x5b1000

Direction changed to upwards: 0x7fe81e1a9000 after 0x5b1000

Non-contiguous mmap: 0x7ffe5255d000 after 0x7ffe501a9000

Last address returned: 0x7ffffc55d000

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ The most important questions going forward are:

- what should we

target? Which regions in the address space are interesting to hit with the unmapping primitive obtained above, creating dangling references in the process? - how should we

reclaimthe memory regions of those targets?

Let’s start with the second.

Reclaiming

A few ways come to mind immediately:

- an allocation that is served via mmap by ptmalloc: this may be the most general option and provide the most control over the chunk contents. However, precision might be a problem: the default value of mp_.mmap_threshold is 128KB, and it also grows dynamically (up to 512KB on x86 and 32MB on x86-64) upon free of a chunk bigger than the current threshold. It’s also never decremented automatically. This means that punching a small, 1-page hole (e.g. .got of a library) and reclaiming it this way seems impossible.

- a library load: i.e. a dlopen. The library will be mapped at the first fitting spot below mmap_base. Take a look at the abbreviated sample code below (from dlopen.c), which simply maps an 8MB anonymous region, unmaps it, and loads the libraries given in the arguments:

void *dlo(const char* name)

{

void *handle = dlopen(name, RTLD_NOW);

...

return handle;

}

int main(int argc, const char *argv[]) {

const size_t size = 8*1024*1024;

void *mm = 0;

void **handles = 0;

...

mm = mmap(0, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0)

...

printf("mapped mm: %p-%p\n", mm, (char*)mm+size);

printf("emulating the arbitrary unmap primitive by unmapping mm at %p\n", mm);

munmap(mm, size)

...

printf("loading %x dynamic libraries\n", argc-1);

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

handles[i-1] = dlo(argv[i]);

// peek into the "opaque" return value of dlopen to get the loaded lib base

// hackish and non-portable for sure?

printf("\tloaded %s at %p\n", argv[i], (void*)*(uintptr_t *)handles[i-1]);

}

...tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ ./dlopen /usr/lib/man-db/libman.so /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcurl.so.4

mapped region: 0x7f44b5050000-0x7f44b5850000

emulating the arbitrary unmap primitive by unmapping mm at 0x7f44b5050000

loading 2 dynamic libraries

loaded /usr/lib/man-db/libman.so at 0x7f44b562e000

loaded /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcurl.so.4 at 0x7f44b4f97000

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ - a non-library memory-mapped file: for example, a player opening a media file. This is very app-specific so I didn’t look into it.

- a thread start: the NPTL pthreads implementation in glibc creates thread stacks using mmap (this differs from the main thread, see below). The default stack size comes from RLIMIT_STACK, which is 8MB on Ubuntu 16.04. nptl_stack.c provides an example of reclaiming an unmapped region via a thread stack, in a the fashion of the previous sample. Note that glibc has a thread stack caching mechanism to cut down on the mmap/munmap calls needed when starting/exiting threads. Stacks of destroyed threads enter the cache, which has a maximum size of 40MB, and unless the user explicitly requested a different stacksize, contains stacks of the default size. If there is a large enough stack in the cache, it will be reused instead of mapping a new region, so this has to be taken into account. Abbreviated source code and output:

pthread_t thrd;

// simply return an address from the thread stack

void *thrd_f(void *p) {

size_t local = 1;

pthread_exit(&local);

}

int main() {

size_t size = 8*1024*1024;

void *mm = NULL;

void *thrd_local = NULL;

mm = mmap(0, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0)

...

printf("mapped mm: %p-%p\n", mm, (char*)mm+size);

printf("unmapping mm then starting thread\n");

munmap(mm, size)

...

pthread_create(&thrd, NULL, thrd_f, 0)

...

pthread_join(thrd, &thrd_local);

printf("local variable at %p, %s\n", thrd_local,

((char*)thrd_local < (char*)mm + size &&

(char*)thrd_local >= (char*)mm) ?

"inside target region" : "outside target region");tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ ./nptl_stack

mapped region: 0x7f36afad9000-0x7f36b02d9000

unmapping region then starting thread

local variable at 0x7f36b02d7f40, inside target region

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ strace -e mmap ./nptl_stack

<SNIP>

mmap(NULL, 8388608, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f3bb5e5a000

mapped region: 0x7f3bb5e5a000-0x7f3bb665a000

unmapping region then starting thread

mmap(NULL, 8392704, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_STACK, -1, 0) = 0x7f3bb5e59000

local variable at 0x7f3bb6658f40, inside target region

+++ exited with 0 +++Unmapping targets

As for unmapping targets, I’ve looked at the following:

- top of the brk heap: unmap the top of the brk heap and grow the mmapped region into it. I haven’t explored this idea thoroughly because it requires high precision and the ability to allocate very large chunks without touching them (especially on x86-64). Also, the old PIE layout complicates things further.

- sections of the binary image: I believe the binary itself is a less interesting target, similarly to the brk heap case above.

- .text section of a library: ptmalloc will never request executable pages, however reclaiming the freed library code with code from another library might be a possibility.

- .got/.data/.bss of a library: seems interesting but to control the contents meaningfully it requires reclaiming via ptmalloc. This means we have to punch a hole of at least 128KB, which may easily hit the .text section of another library, complicating things.

- chunks mmapped by ptmalloc: possibly the most promising of all:

- first, this is a scenario that is likely to give more control over the operations on the dangling references than the others. Let’s stick with an easy case, the controlled target chunk is a large buffer within which we can read and write at arbitrary offsets at arbitrary times.

- second, under certain circumstances, it is possible to force free to unmap such a chunk without knowing any addresses. As mentioned previously, we need to know the distance of the freed chunk and the target region to unmap the target (while also taking care of page alignment). Now imagine two or more large chunks mmapped consecutively, with at least one controlled by us. The chunks will be placed adjacently, from top to bottom, with their chunk headers at page boundaries. If we know their sizes (and why wouldn’t we), corrupting one chunk header and freeing it allows us to unmap the controlled chunk instead, leaving dangling references to it. See blind_chunk_unmapping.c.

- a consecutive reclamation, e.g. the stack of a freshly started thread or a dlopened library, will reuse the target region if it fits there.

- reading/writing the reclaimed region through the dangling references opens up a wide range of possibilities.

- thread stacks: the inverse of the nptl_stack.c example from above might also be possible, unmapping a thread stack and reclaiming it with a large malloc chunk. While this circumvents the stack cache problem of the other direction, avoiding crashes might prove to be tricky, if the thread is scheduled to run in the meantime. I didn’t explore this avenue further.

Note that some items appear on both lists. Mixing and matching from the two lists hints at some fun but likely useless possibilities.

A special case: the main thread’s stack

The linux page fault handler has a special case for expanding the stack until its size reaches RLIMIT_STACK. Basically, any time a page fault happens at an address that’s below the beginning of the stack but within RSTACK_LIMIT, the stack is extended until the page containing the address. This makes it possible to unmap part of the stack and have the kernel magically remap it with a zero page upon the next access. After some experimentation and kernel source reading, it seems that every page of the stack, except the topmost, is fair game. My guess is that this is caused by the way vm areas are split by munmap but then again, out of my depth here.

The main_stack.c sample program demonstrates this behavior. It causes free to unmap the page containing the current stack frames, eventually leading to the ret instruction of munmap accessing the unmapped page, the kernel expanding the stack and the function returning to 0:

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ ./main_stack

p: 0x55df0ec86020, target: 0x7ffe93e9c1c8

p->prev_size: 0xffffd5e07adea020, p->size: 0x2a1f85216fe2

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ dmesg | tail -1

[106641.971062] main_stack[17695]: segfault at 0 ip (null) sp 00007ffe93e9c150 error 14 in main_stack[55df0ce6a000+1000]

tukan@farm:/ptmalloc/madness$ Of course this specific avenue of exploitation seems useless for multiple reasons, including stack cookie checks and the inability to map the null-page in any way, it just serves as an example. While I couldn’t come up with a generic way to leverage this behavior, it may open up some application-specific possibilities:

- messing with cryptographic data: entropy sources, keys

- environment variables and program arguments can be zeroed (assuming they’re not on the top stack page)

- interesting function arguments: think ‘requires_auth’, etc.

Crashes due to nullptr dereferences would likely present significant challenges, though.

Recap

Well, this turned out to be way longer than I intended and many details are still missing. I’ve originally completely dismissed this primitive as useless, in spite of coming across it multiple times while reading the ptmalloc code. After spending some time digging deeper, I won’t say that it’s broadly applicable but it’s definitely not useless.

Comments of any nature are welcome, hit me up on freenode or twitter.